My friend Frank, who drew some nice pictures for the first post in this blog – he’s a lovely man – has got a house in France. It mainly houses spiders and huge, unknown insects that are a cross between a spider and a centipede. It also contained some unexplained black marks on the ceiling downstairs. This isn’t how they got there.

At the junction between the drop – seemingly bottomless and ranged around its circumference with massive totems that seemed something between a fowl and a man – and the edge of the gelatinous tracks, green and viscous, that stretched for miles, jutting down from the horizon in each direction, whose purpose was opaque, the two soldiers had started digging for their lives.

– You should never have done it.

– Done what?

– You know what.

– What?

– It.

– It?

– Don’t try and pretend like you don’t know.

– … But I don’t know.

– How can you not know? It’s why we’re here shovelling. Just leave well alone, I said. You should never forget that every god-forsaken crumb of peat that we relocate from one section of this awful landscape to the other will weigh upon your conscience for the rest of forever. Just remember that, what ever happens.

– Well, then … then I won’t do it.

– … What on earth are you talking about?

– I’ll just stop. I won’t move another bit of earth. If that’s what you want.

– … Are you insane? Or stupid? What do you think will happen to me? When you’re gone?

The other soldier did not answer. Instead, he reached into his pack and took out his tobacco pouch and cork tips and started to roll a needle-thin cigarette. He sat down with a deliberate motion and looked at his comrade. He sat there looking at him for a long time, motionless. When he felt that he had made his point, he took out his field glasses from the pack, and scanned the surrounding country, right to left, left to right. A hollow gesture seeing as they could go nowhere.

As he did this, his companion vaulted over the lip of the ditch, and started to create a barricade of earth around his head, positioning it to protect the base of his skull. Nothing much happened, then, the other let out a scream as his face changed. Darkly-shining light was trying to force its way out of his nose and his mouth, and his eyes. He thrashed around for a time, his body jading in the green glare from his face, until in desperation he picked up the shovel again and hugged it tightly to him. The green light subsided and he sat panting on the ground, the breath wrenched out of him.

– I told you you shouldn’t have stopped.

– Oh shit!

He panted hard.

– I didn’t think it would come on so quick. Or so strong.

– You took the piss bad with it, though. It knew you weren’t just stopping to rest. Don’t do anything stupid like that again.

Their plan was twofold. In order to reach the opening far up in the cliff, they would first have to create a series of stepped mounds, each higher than the last until the alcove in the cliff face had been reached, they would then need to line the whole with flattened earth and thin planks sawn from the twisted mounds of wood that seemed to rise up out of the earth like half-hidden seams of rock. This being done, they would finally be able to convey the relic to its proper place high up in the stuff of the rock.

They had tried many times before to destroy it, but it was unbreakable. They had tried to cast it into the precipice, but it ended up back in their packs. When they stood near to it they felt it prickling the backs of their necks, when they stopped to rest it whispered in its low soft voice to them and they couldn’t help but listen. Eventually both men had to accept that they could do nothing but what it wanted them to do.

* * *

Eustace staggered down the tiny upstairs hallway, unable to lift his legs, feet scraping heavily along the floor. He could feel the bile rising in his throat as he shuffled desperately in the direction of the bathroom. He could smell his own burnt hair, acrid and stinging. His shirt was burnt off to his chest, and on his arm was a black-red tracery of mild burns. Like a skin doily, he thought as he staggered through the door and was sick in the sink. Once he’d finished loudly retching, he was sick in the toilet. This having been done, he was sick in the bath for the sake of thoroughness. He lent on the lip and his elbows made squeaky duck-sounds as he slid on to the floor, curled into a ball and shivered. He lay there for a long time. He could still see Virgil’s face behind his eyes, the image more real now than the face that had left it. Who was he going to get drunk with now? They still had that case of whiskey to finish. He would go downstairs and start on it. What else could he do? He uncoupled himself from the bathroom floor painfully, went downstairs, and drunk himself to sleep.

When he awoke, the first thing that registered was the sting of his burnt skin. It had cracked painfully during the night and had started to scab. He got up and looked in the cupboard for some Savlon, and some gauze. He found half a tube of the Savlon but not the gauze. He took it to the table and started to smooth it over his broken skin, and then made do with the kitchen towel on the table to bind it with. He wrapped the towel around his arm methodically, in order to keep his mind from what it really wanted to think about.

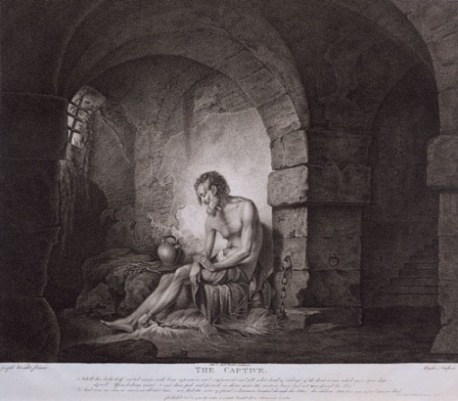

He could see the edge of it through the door from his position at the table, spread out over the ceiling, black and rough. He drank another glass of whiskey, in order to fortify himself, and he let his attention turn to the thing in the living room. He looked at it as he got up from the table and walked into the room. It slowly slid into view as he moved through the doorway – the stark, charred blackness of the radiating marks, the long, thin hole,

and the image of a man burned into the ceiling.

On the left corner of the ceiling, the rectangular outline of the upstairs bed could clearly be seen, with concentric blast marks and stabbed lines of force emanating from it, reaching nearly to the opposite wall. Contained within this was the burned-on outline of Virgil’s body in the position he had been lying, etched like a cave painting into the thick beams – the stick-limbs and box-body like a stylized interpretation of a prone person, the head squatter and squarer than in life. He realised he was shaking and he sat down with his legs out in front of him on the floor, partly to steady himself, and partly to inspect the hole in the floor. This had a similar star of blast-marks around it, and its long, thin shaft descended into the floor as far as he could see. He suspected that it had no end, or not in any sense that he was familiar with. He just sat for very long time. Not thinking about it – he couldn’t think about it – but just sitting because there was nothing else to be done.

Eustace simply got on with things, then. He put a rug over the hole and he just stopped seeing the thing on the ceiling – it becoming as natural as the grain of the wood. He would go to parties, have friends over, and go to work just as he would have done. He never explained the thing to anyone when they came over, as nobody ever asked. They seemed to think that it was some kind of sub-standard ceiling-art, and said no more about it.

One cold day in September he took Virgil’s army trunk which contained most of the apparel of his life into town and gave it to the charity shop. They gave him £30 for it out of politeness, which he gave to another charity shop across the road. Nothing then remained of his friend in the house, and even his memory had been consigned to a dim, subconscious place. He slowly forgot his face.

A year and one day after it had happened, His aunt Olivia was due to stay for a few days, and he tidied up as best he could. At four o’clock when she rapped briskly on the window of the front room as if she had already been knocking for half an hour, Eustace was racked with a dull sense of impending familial purgatory. He opened the door to her and the massive cake-like hat that continually accompanied her. She looked him up and down as though she was surprised in some vague way to find him there.

– …Hello, Eustace …

The barest of perfunctory greetings and she barged her way into the kitchen, and started making herself a cup of tea, her hat brushing the eaves of his tiny cottage. The hat, he knew, really had to be treated as a separate entity. It travelled on her rather than being worn.

– So, how are you then? Are you still working in that tiny little office?

He made a face in his head.

– …Yes. I like my tiny little office.

– And you haven’t ever thought about …?

She stirred her tea once clockwise, once anti-clockwise, and laid her spoon to rest in the sink.

– … something a little bigger?

– But why would I, I …

He stopped himself.

He thought sometimes that if the hat were to be removed, there would just be another of her disapproving faces gazing out from under it, directly up into the sky.

– …Eustace?

She had been saying something.

– What? Sorry?

– I said how’s Virgil? Is he here right now? I should very much like to talk to him about his tour of Namibia.

Eustace braced for impact. He would just get it over with.

– Come into the living room, Aunt Olivia. It will be best explained in there.

He got up and she followed hesitantly, still clutching her steaming tea.

As she entered the room, she looked as if she would make some kind of derogatory comment about the state of the place, but he held up a hand to silence her. She was not at all used to being silenced, and so was quiet.

– Just look up there.

He nodded to the corner of the ceiling.

– Well, it certainly has an ethnic quality, but the style is a little unpolished. Where did you get it from? You’ve probably been hideously scammed.

– Virgil’s not here because he was possessed, Aunt Olivia. I tried to save him, but he just burnt away in the upstairs bedroom. Those marks are where he succumbed to the demonic host. I gave his stuff to the charity shop. I got £30.

She looked at him for a moment.

– … Well, you can’t just leave it there, It looks ghastly. I suggest you paint over it by the end of the day. Three coats, just to be sure.

– … Yes … Aunt Olivia.

– I mean, …

She inspected the marks with narrowed eyes, and stepped carefully over the hole in the floor.

– … Have people been coming round all this time to this mess? It’s a wonder they come back at all. I’m going to the shops for sugar, do you want anything?

– … No.

– I can put it on my card, it’s no trouble? I won £50 pounds on the lottery yesterday. I can splash out? … No? … Suit yourself.

And she barged through the door and was gone.